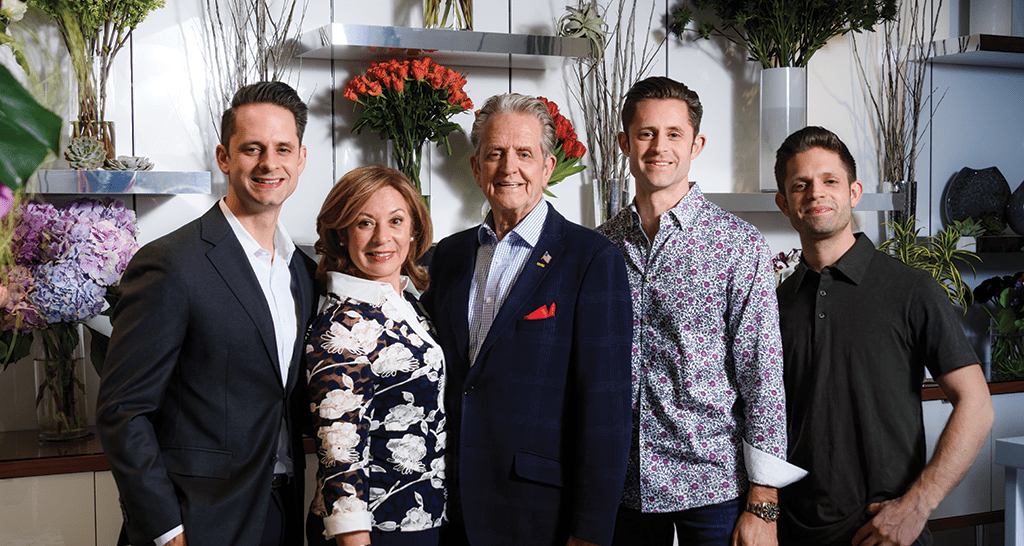

The Palliser family’s efforts to reinvent their longtime floral business are captured in the February 2020 issue of Floral Management. Photo by Donnelly Marks.

When the Palliser brothers came together in 2015 to help find a new groove for their family’s longtime New York business, they faced increased competition, high customer expectations and a changing retail landscape. This month in Floral Management, we chart how the family rethought everything at Scotts Flowers, raising online and walk-in sales by double digits in the process.

In many ways, Scotts Flowers in New York City has had way more than one life. The original company, pioneered by the Scott family, opened in 1947 — back when the average American house cost about $6,600 and the average worker made shy of $3,000 a year. In 1982, Robert Palliser Sr. purchased the business and pushed it into a new era. The Vietnam War vet introduced new technology and faced fierce competition — including the intense expansion of supermarkets into the floral market. He and his wife, Silvana, also raised three boys — Rob Jr., Chris and Jonathan — who spent their childhood (like so many kids in the industry) learning about the business of flowers, even when they weren’t sure if that business was for them.

And yet something about the retail operation eventually pulled all three of the Palliser brothers back. Rob pioneered the next generation, officially joining Scotts in 2011 and learning the business from the inside out. Chris took a different route, working in finance from 2011 to 2014, before Rob asked him to consider working at Scotts. By that time, their father was thinking seriously of retirement, and Rob Jr. knew he needed a right-hand man to help keep the business on track and prep it to face a host of new challenges, including the advent of online ordering, proliferation of floral competitors — and sky high consumer expectations. When Jonathan graduated from college in 2015 and came onboard, the trifecta was complete. The brothers were ready to build on their family’s hard work and leave their own mark.

End of story? Not even close.

Because while the Pallisers could thank their father and mother for a strong foundation, the job of keeping the business going, and pushing it to new heights, now fell squarely on their shoulders. And there was work to do: a brand refresh, tech upgrades, a major staff shakeup — and an overall repositioning of the business to better meet the demands of modern consumers.

“Our parents’ work ethic really inspired us, and our father implemented this team spirit attitude among us as brothers,” Chris Palliser said. “But we get agitated when things are complacent. We’re always trying to grow and learn more.”

History Plus Innovation

The fundamental challenge the Pallisers faced likely feels familiar to many floral pros: How do you take the best of your past — your experience, the goodwill in your community, your team’s knowledge and skills — and leverage it with new ideas and outside perspective? Can you create a workplace where traditions, history and founders exist right alongside novel ideas, innovations and status quo disruptors?

The short answer? Yes!

The more nuanced response? Yes, but…

Creating that positive past/present/future dynamic requires compromise, hard work, team players, mistakes, learning time, practice, dedication and vision. Nonetheless, it can be done, according to two very different floral businesses who have embraced entrepreneurial thinking in a big way — and seen sales, website and foot traffic, customer engagement and employee morale improve as a result.

Lesson No. 1: Structure is your friend.

The picture many of us have in our head of an entrepreneur/startup founder/disruptor: A freewheeling guy or gal who isn’t bogged down by red tape and rules.

The reality? Formalized processes are often the not-so-secret ingredient behind the launch of a successful idea — or the continuation of a longtime business.

Building stronger structures was a focus for the Pallisers. When the brothers took over in 2015, they realized their 25-person team wasn’t operating from the same playbook. Sales team members were underselling. Designers were modifying recipes. Customer interactions sometimes seemed clipped and transactional.

“No one wants to see a note from a customer first thing in the morning that an order wasn’t delivered,” Chris Palliser said. “Things were falling through the cracks. We wanted to find a way to limit mistakes and keep up with customer demand and expectations.”

Rob, Chris and Jonathan had a different vision — of a business that hummed along (profitably) and employees who felt empowered (and encouraged) to try new things and connect emotionally with their work and their customers. To get there, they needed to set up some guardrails to keep their team on track.

So, they started experimenting. They attended industry events and educational sessions — including several from the Society of American Florists — and hired an outside company (FloralStrategies) for customer service training. They learned to unlock tools in their POS system — they use GotFlowers — and to identify common mistakes in the design room and among the sales team that drained profits (for example, offering price points to customers tentatively instead of making expert recommendations).

They also introduced formalized weekly or biweekly meetings for each department (sales, design and customer service). Each 15- to 20-minute session gives employees focused attention from the Pallisers and dedicated time to troubleshoot issues, brainstorm solutions and set goals. Every two to three months and major holidays and projects, they also convene an all-staff meeting to discuss logistics.

Of course, changes can lead to friction. Since the Pallisers began implementing these changes, they’ve seen many staff members move on — in fact, it’s been almost a complete turnover, according to Chris. “There was no mass firing or anything,” he explained. “People just realized they weren’t a good match.” But new hires have also brought new opportunities, including designers who are excited to share tips about mechanics and techniques — and who also are receptive to learning new things from others. “A few good eggs led to more,” Chris said. “We hire for personality.”

Katie Vincent Hendrick is a senior contributing writer and editor.